Stephanie Snyder

Dear Aaron,1

No sun rises to cast aside love of an idea or a new form of misery. These wait patiently for sunset, dear luminous twilight, at which time in a kitchen that has become Portland Oregon’s egalitarian andron (see note 4), through conversation, food, music, text and the jostling of bodies, we convene to explore somatic and intellectual conviviality. For almost a year now, lead with measured recklessness by our symposiast Matthew Stadler and feuled by Michael and Naomi Hebberoy, whose tiny culinary empire, so appropriately named ripe, forms the habitus of this experiment, we have eaten, disagreed, listened, and kissed. This practice is called the back room, and it has roots as ancient as digestion.

a.

To lie together, ill formed and unconstrained–forthcoming. Our desiring rules, our measuring stages…unchecked decency threatens to violate our symposia.2 We must strigil our desire off the knobby heads of our fathers, untangle ourselves from the dusk of their pungent curls.3 They, for their part, must swell a discussion of the feast into each dim hour uncolored by certainty. The committee must wind the Panathenaic robe of consensus round our bodies–embroider each dissonant opinion into the folds of our civic garments until we collapse under their weight like moths. The committee must redouble its efforts to protect the komos, advance this imperative [illegible] and support oratory throughout the entirety of the evening. I disgust at the committee’s lack of recognition for the length of time that such measured meals demand…at the committee’s poor wages, pornographic uncertainty, and, presciently, for the discomfort they will cause me. To drizzle a steady mist of gold onto those who would rule over others poisons the very air. Alcibiades mutilated the Hermes because he could no longer stomach such gross insousciance.

b.

Each of you, three klinai from the other.4 You brush Alceon as you adjust your pillows. I gaze upward, my desire reaching to your neck, hoping this time to kiss your clean, clear chin, strong like your son’s and fire-lit. Hestia said that tonight’s feast honors Alceon’s new poems. Tonight everyone will eat well; Alceon is rich and vain. The braised meat hanging from your table soothes the air near my face, seeks my nostrils. They chant again THE DIVINE ARE AMONG US and twirl and raise their silver to lyric Apollo and drunken Dionysus, and to Athena for her feasting of Heracles. I do not like this. The divine bring terror when I have been tasted by every man in the room and the eye of the kylix stares. If your cock or his cock moves any faster next time I will faint. Come the boys, I forgive [illegible]. I say it out loud but then I do not hear you. And now I am laying into myself on the softest hide under your couch, and my mind is shadows and pictures…your son bent under your best friend’s grasp, you transfixed by the breath fluttering through your son’s lips, his sudden gasps…I know this happened, I desired it so, I sweat upon it through the familiar roughness of my own hands…Syron trickles wine on my face, it races into my mouth and I come.

c.

The Ethiopian, they call him–the afterimage of the sun-god himself curses his skin–blackness upon blackness–a funeral pyre of castings. But no barbarian the Ethiopian is, he knows his Greek, he knows Greek to the touch. With disdain, and outside of the sanctions of the Agora, too often Solon auctions the Ethiopian, secures him to attend Alceon’s symposia, conspiring that Alceon and his little bitches will beat him, grimacing into sunrise.5 Solon knows the Ethiopian cannot take his wounds to the law, cannot petition his case to the courts, regardless of his Greek, as he is a mute absence in the court’s [illegible]. To so abuse the Ethiopian, to douse his head with lamp oil and twist his collar until dappled shards of skin float on the air like cherry blossoms, Solon and his heterai delighting in feigned surprise that beneath the Ethiopian’s blackness a bleeding pink cunt emerges, to laugh at the Ethiopian’s furtive blood outside of citizenship and mercy, we say aloud, is to disrespect divine intent–DIVINE. To thrust ourselves, one after the other, into the mouth of the Ethiopian, must we not allow him to know–even at the last minute–the language of the deme? Can we so completely constrict his mouth from the petition of law? I saw the Ethiopian at the last moon rites for Hephaestus; he was there with Kallikrates, his hair clumsily shorn. In fact, I saw his hair first, earlier in the day, in Solon’s possession…he was holding forth at the Stoa on the creation of strength contests in Athena’s honor at the next Panathenaia. Solon had cushioned the head of his walking staff with the Ethiopian’s curls, bound them underneath a swath of leather like the head of a tortoise. Was it for comfort, I asked Solon, or the lingering memory of a dim encounter, such as the time I saw him kiss the Ethiopian’s cum-stained lips, shuddering under him like a boy–poor man’s silver, poor man’s gold. Solon lifted his staff to his nose…”To the courts with you, cunt [illegible].” “To the sheep with you, Persian, to the feet of women.” Were I younger and possessed of honeyed tongue, I would challenge his arrogance–and his poetry. To be just is an art, but to create art, how is it that one such as Solon can scuttle so easily into the realm of Apollo, dear mouse, while diverging so completely from justice?…How often Proton and I have lamented that we have forsaken cautions against the arrogance of art. Solon’s psyche climbs the candlelit walls and distorts into demons that I do not wish to become.6

d.

The komos surrounded the flute player after he came across the tables and his cum soiled the food. I turned to my right and out the wall drain I caught a glimpse of the mistress of the house and her daughter in the moonlight. The black slave was watching the road. I know whose horse they were expecting. The boy was dizzy from coming, and to taunt him Lyceon hid his right hand and offered his left hand to the boy in greeting. When the boy bent to kiss Lyceon’s ring, Lyceon grabbed ahold of his chin, drew his right arm around, and hit the boy in the eye with a ball of meat.

e.

The mistress’s father was exiled from Athens to Thebes for buying votes for Alcibiades. It will take four days for a letter to reach her father, and five days for one to return because of the east hills. I have heard stories about the beauty of the wheat fields in Thebes from the old woman who lives with the whores, near theAgora. Praise Athena, she grew up in Thebes and outran Xerxes into the city. This woman is so old that the dye will never leave her fingers. She has a wooden figure that looks like a satyr’s cock. She covers it in olive oil and sage and works it into the assholes of the whores. She’ll do it for me if I ask her to. Glasses are raised, THE DIVINE ARE AMONG US. Visitors arrive from Kaliti’s symposion. My lover Dion is with them. We give each other a smile and, seeing this, Alceon blows a sour eye at me from across the flame, scattering burning oil onto my back. Alceon waves Dion to him, my beloved, and slides his hand between his robes. He moves it in and back as he cups Dion’s balls, the smooth fuzzed treasures that I consider my [illegible]. The fabric falls away as Alceon instructs me to drizzle his best scented oil–the oil he won in competition!–onto Dion’s cock, which bobs, smiling stupidly like a Herme.7 Alceon doesn’t take him in the ass. He coos and frets over Dion like a woman weaving until Dion’s eyes roll back in his head and everyone laughs. I see the youngest servant watching from the corner as he mixes the wine. I will find him later. He will learn that it’s better to be fucked in Athens than beaten in Sparta.

f.

Cleobis and Biton, dear twins, as sweet as wine bearers.8 Their mother, so fortunate to implore our terrible gods’ blessings, wished, alongside every good thing and true, alongside happiness, that her hand-washed boys might unfurl with joy and live the rest of their lives content…and they died, flopped on the road under her cart. They died, asphyxiated by happiness.

NOTES

1. To engage well as a symposiast was to embrace the aesthetic responsibilities, dangers, and pleasures of Greek citizenship. The Attic symposion flowered and died as Greek society changed, but before all things, it was aristocratic…conducted by and for the most privileged men of the culture. So know that first. But Aaron, know that your kind invitation to write an essay about the ancient Greek symposion has resulted in a lengthy translation of the sort that I have not completed since living in Athens. It is good and feels somehow redeeming to flex these particular muscles right now, during these depressing political times. There is so much I want to tell you about the astonishing institution of the symposion…a space of intimacy, art, and violent political agency. The texts in this essay are loose translations of several groups of fragments: one from a collection of fourth-century B.C.E. letters later recounted by Alciphron in 200 C.E. Alciphron’s “letters” contain our most reliable personal descriptions of sympotic space…the letters often appear to be from the perspective of a prostitute, about whose sex scholars do not agree. The second primary texts are fragments of legal proceedings from the deme (political area) of Athens from approximately 590 to 370 B.C.E.

2. Distinct from public religious rites, or larger, more inclusive civic feasts, the sensual intimacy of the symposion followed a larger meal, though breads, meats, fruits, and other delicacies were served along with wine, which the Greeks considered to be their most significant cultural accomplishment. In this case, wine was mixed with the freshest of rainwater–the proportions of which were determined by the symposiast–the host, or patron of the feast. Wine and water were mixed together in large standing vessels–kraters–often by a slave but often by the household servants brought to the feast by guests. These citizen men who died together by the thousands during each warring invasion and who kept their wives under the strictest prohibitions–these men were the government, the military, the cultural fabric…The symposion formed their most intimate discursive space–a civic yet private arena, reserved for the performance of contemporary and archaic poetry, lovemaking, fucking, and the raucous bruise of violence. The symposion served a pedagogical function in the education of younger aristocratic men–morally, intellectually, sexually. Scholars argue that the nature of the latter Attic symposion–the symposion primarily witnessed in these texts–evidences the decline of the aristocracy as the center of political power (its role as the warrior class slowly eroded by the implementation of the professional Hoplite army).

3. The connotation of this passage is definitely the castration or the violation of the father by the son. A strigil is a curved implement–often silver, copper, or wood–for scraping excess anointments from the skins. The scraping action also acts as an exfoliant. Many existing examples have handles in the shape of penises, presumably for sexual use.

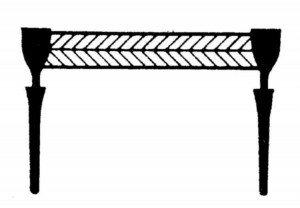

4. The symposion was conducted in the confines of the andron–the private men’s room standard in a privileged Greek home. Either square or rectangular and always with easy access on the ground floor, theandron was constructed to house no more than twelve klinai, standing wooden couches, on and around which the symposion flowed. A standard klinai held two people comfortably, each party resting in the opposite direction (foot to dick, they called it)…the second place reserved for intimates and hired entertainment. The andron’s size ensured that the participants could hear one another without shouting. Each guest was meant to be no more than three couches distance from any other…It was critical that each symposiast be able to discern the aural nuances of poetry and debate while reclining comfortably on his pillows and hides. Because poetic recitation was one of the centerpieces of sympotic activity, the subtlety of this aural embrace was legally protected.

5. The sympotic banquet lasted beyond night into dawn, and often symposiasts roamed betweenhouseholds. We know from textual sources that symposia often ended violently. The komos–the rowdy, drunken group of symposiasts (visible naked on vessels of the period and usually accompanied by musicians or attendants)–spilled out of the andron and into the streets, destroying ritual and civic property, accosting homes and people.

6. Ironically, it was Solon himself who decried that Greece’s political agency was being eroded by the citizen’s inability to conduct restrained and measured feasts. In the Eunomia (c. 580 B.C.E.), Solon writes:

It is the citizens themselves, who, in their folly, wish to destroy the great city in yielding to the lure of riches, and likewise the unjust mind of the chiefs of the people, those who prepare great evils for themselves and their great excess. They do not know how to restrain their greed or how to order their present happiness in the calm of a feast.

7. Hermai are large standing stone statues–erected in front of homes, in public thresholds, at geographic crossroads–the tops of which contained carved portraits of the god Hermes (god of travelers), the squared bottom of which contained large erect genitals. In 415 B.C.E., the night before the Greek navy was set to sail into and conquer Sicily, Athenians awoke to find widespread mutilation of these sacred statues. A great public crisis ensued. Many people, like the author of this political invective, believed that the mutilation was conducted by a komos led by Alcibiades, pupil of Socrates, raised by Pericles after his father was killed in battle. Alcibiades was sentenced to death, but escaped to Sparta and found his way back into Athens’s graces. Socrates himself initiated Alcibiades sexually at just such a symposion.

8. This fragment, from Alciphron’s letters, recounts an ancient story of fidelity, familial piety, and the gods’ passion for thwarting the hopes of mortals. Standing carved figures of the twins, created between 610 and 580 B.C.E., are housed in the archaeological museum of Delphi.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Frazer, Ian. “Beasts and Beauty.” In the New Yorker, December 12, 2005.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters on Cezanne. Translated by Joel Agee. San Francisco: North Point Press, 2002.

Robertson, Lisa. Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft Architecture.

Astoria, OR: Clear Cut Press, 2003.

Schmitt-Pantel, Pauline. “Les repas au prytane et à la Tholos dans l’Athènes classique: sitèsis, trophè, misthos, réflexions sur le mode de nourriture démocratique.” In AION 11, 1980.

Stadler, Matthew. Allan Stein. New York: Grove Press, 1999.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Klinai from scenes on Attic Geometric vases. From: Laser, S. (1968) Hausrat

(Archeologia Homerica, 2 P; Göttingen).

This essay is one in a series commissioned and published by the back room, Portland, Oregon, curated and edited by Matthew Stadler. The essays are published in modest well-made chapbook editions and will later be compiled as a bound anthology.

The back room is an occasional series of presentations/symposia/bacchanals that take place in the family supper room of ripe, a restaurant in Portland, Oregon, replete with food, drink, music, and general boisterousness garlanding the central pleasure of bright intellects voicing their excellent texts, winging it in conversation, and screening or presenting various textual and visual delights.

Copies of “Letters from the Symposion,” in a chapbook edition from the back room, Portland, Oregon, are also available for sale at Reading Frenzy, Motel, and Powell’s, Portland, Oregon, and Modern Times, San Francisco.