Christopher Brayshaw

AND TO STOP YOU INTERFERING, I SHALL HAVE TO DEMATERIALIZE YOU AGAIN

REVIEWED BY CHRISTOPHER BRAYSHAW

And To Stop You Interfering, I Shall Have to Dematerialize You Again

Catriona Jeffries Gallery

3149 Granville Street, Vancouver

Through 10 November 2005

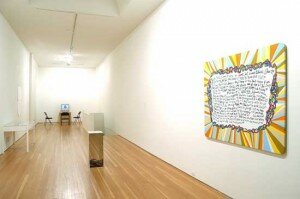

Installation view, Catriona Jeffries Gallery. Photo: Scott Massey

A statement on the Catriona Jeffries Gallery website says the gallery exists as a presentation platform for “current manifestations of post conceptual art practices in Vancouver, as well as the origins of conceptualism in Vancouver.” I don’t know how this thesis accounts for the gallery’s representation of artists like Arni Haraldsson, Brian Jungen, or Jerry Pethick, whose works seem only tangentially related to conceptual, postconceptual, and neoconceptual art, but it certainly applies to the objects displayed in this sparsely installed and intellectually rigorous exhibition, which consists of pieces by two Vancouver-based artists (a painting by Alex Morrison and a video installation by Isabelle Pauwels) alongside a sculpture by Cologne’s Johannes Wohnseifer and a mixed-media work — or works — by Los Angeles-based Frances Stark.

The exhibition’s overt avowal of imagery immediately announces its relationship to orthodox conceptual art, and the works on display largely employ materials and techniques that directly refer to the “look of art” circa 1967-1973 (manual typewriter typeface reproduced by inky purple ditto machine; painting executed not as “painterly” object but as sign painting by a hired hand; mirrored column; uncomfortable chairs, wooden table, and tiny TV set).

In many contemporary artists’ hands such strategies merely amount to mannerism, the unthinking reanimation of a period style. The nagging sense of dissatisfaction I feel whenever I study the work of Sean Landers or Annika Ström is largely motivated by the suspicion that their work consists of the uncritical repetition of a “look” that passed out of favor more than thirty years ago, instead of the ongoing analysis of the philosophical and aesthetic issues that led to art’s dematerialization in the first place.

Ambitious art must always be true to its own time. Common sense implies that works made by the contemporary heirs of artists like Robert Barry, Lawrence Weiner, Sol Lewitt or Douglas Huebler should look nothing like that of their intellectual parents, merely by dint of being made in 2005 and not in 1970.

Art exists, of course, to complicate rationally arrived-at decisions, and one of the lovely ironies of this tightly focused exhibition is how closely its strongest works hew closest to the “look” of classic conceptual art. Frances Stark’s and Isabelle Pauwels’ works preserve both the appearance of vintage conceptualism (blurry manual typewriter typescript in a vitrine; ultra-low-budget single-take video running in real time) and the formal and intellectual rigor of the best conceptual art.

On the other hand, Alex Morrison’s text painting — which borrows its words from a contemporary rapper, and its design from indie music or skate culture, and thus is more stylistically up-to-date than either Stark’s or Pauwels’ work — disappoints, seeming strangely vacuous and unengaging. In this way, the first hand experience of evaluating art – looking, comparing, judging, and looking again — proves its superiority to rational theorizing.

Isabelle Pauwels’ video installation Making a Living is, to my mind, the best piece in the exhibition. It’s leavened, as is all of Pauwels’ work, by the artist’s dry wit and flawless recreation of a “period style” – in this case, the chair, table, and direct address of Vito Acconci’s 1972 performanceUndertone. Over the course of the hour-plus video, Pauwels tries to ingratiate herself with you; rejects you; flawlessly delivers her lines; hopelessly flubs her lines; masturbates a la Acconci; apologizes for dramatizing “someone else’s fantasy”; delivers a series of pointed one-liners; rambles pointlessly, and, finally, lapses into sullen silence, staring unhappily at the camera, exhausted, until the only proper response is to drop your eyes and walk away.

Pauwels’ video isn’t fun to watch by any stretch of the imagination; I was bored, irritated, aroused, embarrassed, amused and provoked in turn. You sense you’re being manipulated, but you don’t walk away; the work’s affect is such that it traps you for over an hour in an uncomfortable chair, even as you keep shifting and telling yourself that you should leave. Pauwels’ point, if I understand her right, is that good art creates a brief imaginative sympathy between artist and viewer, a temporary pact transcending the class divisions that alienate producers from consumers. Pauwels is under no illusions that such pacts will effect any kind of revolutionary social change – she is too much of a realist to ever lapse into vulgar Marxism or relational aesthetics – but her work holds out the dim hope that such pacts may in fact be materializable in other ways than purely aesthetic ones.

I admire Pauwels’ dry humor and conceptual rigor; much of her work is formally off-putting or acerbic, and I like its air of tart critique. Many artists are at pains to ingratiate themselves with preexisting power structures. I can’t think of a less ingratiating artist than Pauwels, and I admire her refusal to entertain or perform. To paraphrase one of her better lines, an artist need only be capable of saying one thing: NO. Pauwels has made an exemplary career of NOs.

Johannes Wohnseifer’s work consists of a half-transparent, half-mirrored plinth, inside of which the letters of the artist’s name sit in colored vinyl. This piece nods at the work of Dan Graham, Robert Smithson, and, perhaps, some early pieces by General Idea. It is also totally uninvolving, the equivalent of Duchamp’s ideal readymade, a work incarnating the total absence of good or bad taste. At least Duchamp had the good sense to pick visually complex objects as readymades; Wohnseifer’s sculpture, on the other hand, doesn’t lend itself to either extended aesthetic or intellectual reflection. The half-transparent plinth obviously refers to the artist’s body; so too do the letters enclosed within it. What isn’t clear is why the work takes the form it does, or the considerations that have led the artist to use a by now thirty-year distant formal vocabulary. Juxtaposed with similarly autobiographical works by Pauwels and Stark, Wohnseifer’s piece seems derivative and thin.

Frances Stark contributes a paper sculpture – several sheets of paper and tissue hung from the wall, adorned with handmade marks and a little photographic cutout of a bird. The work is visually slight, very much in the spirit of Arabella Campbell’s monochrome paintings – also recently exhibited at Catriona Jeffries — which efface the distinctions between art objects and the architectural container of the surrounding gallery.

Stark’s work also comes, in the spirit of conceptual art, with its own exegesis – typewritten instructions which are part diary, part instruction manual, and part philosophical speculation on the work’s ontological status. I like the minimal rigor of Stark’s paper sculptures, but I admire her written exegeses of them even more. Certain recent art-historical texts on conceptual art (Buchloh; Wall’s notorious “authority of the crypt”) have attained the status of objectivities by focusing attention on the movement’s relationship to bureaucracy and administrative culture. What is lost in these critiques is how funny much conceptual art really was – Broodthaers’ autobiographical confessions and assumptions of multiple personalities (poet; painter; sculptor; director of an imaginary museum); Douglas Huebler’s unrealizable projects; Weiner’s removals and alterations, so banal as to resemble a sculptural poke in the eye. Stark’s writings maintain conceptual art’s dematerialization of art-into-life by depicting art as an activity that occurs alongside other human activities – thinking; criticizing; talking to friends – but also admit emotions typically suppressed or censored from “advanced” art: humor; uncertainty; the artist’s own conflicted judgment and analysis of supposedly “finished” works. Stark’s art is open in the best sense of the word.

Finally, there is the problem of Alex Morrison’s large sign painting. It doesn’t matter that the painting’s text is appropriated, or that the work is executed by a hand other than the artist’s; these strategies are in keeping with conceptual art’s de-emphasis of the artist as a skilled producer, someone with a special talent or lucky touch distinguishing him or her from others. What matters, and consequently damns the work for me, is the way in which Morrison has constructed it to anticipate and refute critique. You can read its slick and breezy hand-lettered text autobiographically, in which case you accept the artist as the cynical, cocksure young rapper kickin’ it underground for his peeps, even as he knowingly permits the exploitation of his image by power; by commerce; by everything, come to think of it, that Isabelle Pauwels’ work stands in opposition to. Or, conversely, you can read the painting as making fun of its text’s tarnished idealism, acknowledging that the artist, like the musician whose words he’s appropriated, has already sold out.

Morrison might argue that his painting proceeds dialectically; that it holds both positions simultaneously, and is only forced into one or the other by critical judgment, by a viewer’s own subjective biases. I don’t accept this lazy excuse for openness any more than I accept Morrison’s blatantly flaunted insecurity as the conceptual motor that makes his work run. It seems Morrison only wants us to admire him for his idealism; or revile him for his cynicism; or in fact to think of him with any kind of strong emotion at all. But art doesn’t merely depend on a viewer’s good or bad opinion of it, and Morrison’s bad-faith attempt to argue otherwise is a misguided misreading of the challenges conceptual art mounted to aesthetic consensus by breaking down preexisting critical categories, instead of simply subsuming judgement to them. This project is an ongoing challenge that animates and drives Stark’s and Pauwels’ work; their art’s complexities, in turn, highlight what is lacking in Morrison’s and Wohnseifer’s own.

Christopher Brayshaw is a multiply-hypenated Vancouver-based independent critic-curator-bookseller-photographer.