Charles Mudede

BIG TREES OF SEATTLE PART III

CHARLES MUDEDE

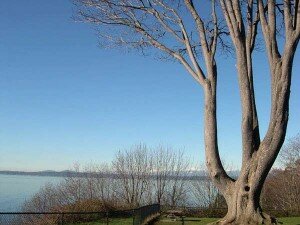

We were on a picnic table. I was inside of you, and amazed by the shape you made of me. Behind the fixed table supporting our fucking and fumbling was a row of magnificent magnolias, the orange-reddish trees that named this small park, Magnolia Park, which is 12.10 acres, on a bluff (Magnolia Bluff—address 1461 Magnolia Blvd W), and designed by the stepson, John C. Olmstead, of the man who designed New York’s Central Park, Fredrick Law. John Olmstead planned Seattle’s park system, and so many of the biggest and most beautiful trees are only here because of him. Magnolia Park stands as his masterwork. It has a restroom that’s straight out of “Hansel and Gretel,” and covered by the type of shadows that carpet forest floors. A gentle slope falls from the fairytale restroom to the picnic table, which looks out at the sea, the island, the falling sun, the volcano just beyond the city. One moment in lost time—late in the summer, late in the day, dusk on its way, ships on their way, planes coming down, stars coming out—we were then and there as close to one as humans can ever become.

According to someone who knows his stuff, the big tree near the picnic table is a Finnish oak (someone else who knows his stuff says it’s a big maple leaf). This is all he could tell me about it. But anyone who has the time to visit this perfect little park by sea (our kingdom by the sea) will see that it is what it is: a very big tree. Its main branches reach for the sky with an enthusiasm you might find in the mind of man who thinks that the sky is really something. The tree’s roots are muscular. They don’t love the earth as much as make sure it’s not going anywhere soon. The roots refuse to trust this park, this ground, this spinning world. The roots appear to suffer from an acute sense of the impermanence of things. But instead of surrendering to the hard facts of life, which is exactly what a dandelion is all about (a total surrender to the slightest force, the slightest wind), the roots of this Finnish oak are holding on with the might of a terrified giant. But the tree’s top is graceful; it seems to be charmed like a dancer from a distant place with a fierce sun, black markets, and formidable reptiles. The tree is at once graceful and desperate. Its top wants the freedom of the sky and its base wants to stay forever in the earth of the park designed by Olmstead.

After that summer-warm night, my love, wherever you are now (“in minus time-space or plus soul-time”), I did not mind returning to the park the next morning to look for the earrings you misplaced during our bursts of fucking. (They were so important to you; a gift from your dying grandmother.) Though I did not find your ornaments, I did discover, in their absence, and in the general emptiness of the awakening park, what was soon to become of what we were to each other that summer: a place in the future where the sun will no longer be. I will always love you and big trees.

Charles Tonderai Mudede is an associate editor for The Stranger. He was born in an Africans-only hospital in Que Que (now called Kwe Kwe), Rhodesia (now called Zimbabwe), in 1969—Kwe Kwe was, and still is, a steel town, much like Charles Dickens’s Coketown. Mudede is also an adjunct professor at Pacific Lutheran University, and his work has appeared in The Village Voice, Sydney Morning Daily, and The New York Times, among others. Mudede reads Lolita at least three times a year.