Charles Mudede

BIG TREES OF SEATTLE

CHARLES MUDEDE

Big trees amaze me. They rise up into the open sky and spread out, covering a wide area of city life. During the summer, when big trees have all of their leaves, each is a total universe—a self-contained, self-governed, self-determined society of critters, birds, fungi, and tiny insects that go about their tiny business in the shallow and deep grooves of the bark. Cutting down a big tree is the same as wiping out a whole city, which is why a powerful chain saw is to a big tree what Hurricane Katrina was to New Orleans. In an instant, an entire economy is gone, and exposed insects are stranded, and stunned birds go crazy in the massive absence of what was just there—a big tree.

When one walks beneath the breathing branches and bark of a big tree you are not entering a spot of shade but a whole other world, a realm with its own climate, quality of light, and sounds of the night. But despite their impossible size, big trees almost go unnoticed in our big cities. Only arborists give proper attention to these living things that take up so much space and have been around for as long as anyone can remember. This article, serialized over the next three months, will explore and describe the ignored giants within the limits of the city of Seattle.

Because being big is the essential feature of a big tree, we shall begin with a tree whose inessential features have been entirely removed. This tree is nothing but big.

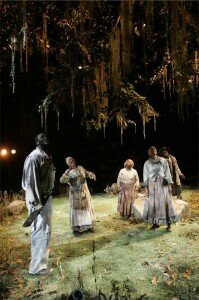

The tree that concerns the present column is not only inside of an old, stately building (Kreielsheimer Place) on the corner of 7th and Union, it’s also fake—nature’s role in its making was for the most part indirect. A man, a set designer by the name of Matthew Smucker, is directly responsible for this particular tree. He designed it for the realization of a play titled Flight. Set in 1858, on the edge of a plantation near Savannah, Georgia, Flight has five visible characters and two invisible characters. The play begins with the visible characters rushing onto the stage, looking for a missing (invisible) boy named Li’l Jim, whose mother, Sadie (also unseen), was sold that day by her owner as punishment for teaching the boy how to read. The five black slaves, one of whom is Li’l Jim’s father, find him in the big tree, which according to the program notes is modeled after a pecan tree. Attempts at convincing the traumatized boy that it’s safe to come down from the tree propel the play’s plot.

Unlike big trees in the real world, the tree on this set has no life in or on it. Nevertheless, it is impressive, with thousands of green leaves fictionally nourished by the suns of ten or so spotlights. And what a trunk this tree has! Indeed, it’s by no means easy to believe that immediately after November 13th (the end of Flight’s run), the whole damn thing will be dismantled and replaced by another prop for another play. Big trees, especially fake ones, have a presence that is larger than life.

Charles Tonderai Mudede is an associate editor for The Stranger. He was born in an Africans-only hospital in Que Que (now called Kwe Kwe), Rhodesia (now called Zimbabwe), in 1969—Kwe Kwe was, and still is, a steel town, much like Charles Dickens’s Coketown. Mudede is also an adjunct professor at Pacific Lutheran University, and his work has appeared in The Village Voice, Sydney Morning Daily, and The New York Times, among others. Mudede reads Lolita at least three times a year.